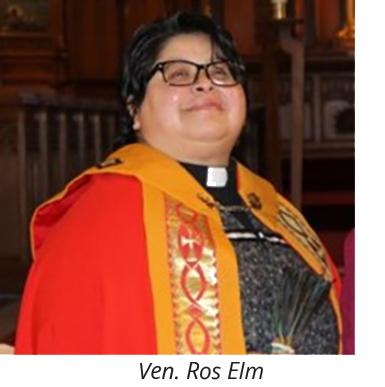

Presented at 185th Synod of the Diocese of Huron (October 19, 2024) on behalf of Huron Indigenous Ministries Team, and on behalf of Ven. Rosalyn Kantlaht'ant Elm, Archdeacon for Reconciliation and Indigenous Ministry

By Rev. Hana Scorrar

WE WERE ASKED by Bishop Todd to speak to the theme of where we are in Indigenous Ministries and what we have learned. I think the things we have learned could fill the entire day with discussion, but I hope to offer a few thoughts on how Indigenous Ministries has been shaping itself in new ways and how they might inspire reflection and exploration for the rest of the Diocese.

Firstly, before I dive into any of this, I need to profusely thank the team we have been working with the past year: Elaine Burnside, John Paul Markides, Maggie Weigers, and Leah Arviddson, and a special thank you to Sam Thomas, who while not a part of the team technically, was certainly one in our hearts; these amazing leaders, along with the remarkable lay leadership that exists in Zion Oneida, St Andrew’s Chippewa-Muncey, the Parishes of the Six Nations, and St John’s Walpole, have made this journey that we are on incredibly rich and meaningful. Without their help, Ros and I would not be able to accomplish the amount of work we have done. And they all, clergy, students, and laity, have been a blessing to us both, in more ways than they can probably imagine.

Their passion for their ministries, their willingness to dream big God sized dreams with us, their flexibility and enthusiasm for chaos and experimentation, and most importantly, their ability to work cooperatively, are really and truly why I can stand here this morning to tell you about the revival we are experiencing in our Indigenous communities.

And that’s where I want to start: collaborative ministry and community building.

Since Ros and I first began this journey together as priest and archdeacon, we have held at the centre of our work the need for collaboration and relationship. Particularly relationship that echoes traditional ways of knowing and being; relationship build on trust and love, vulnerability and courage. Our team, whatever the iteration, had always been founded on lateral or transformational leadership; with the emphasis on giftedness and empowerment, rather than hierarchy. We view our specific roles as a function of the ministry, a responsibility to each other, and as relational to the community.

This is fundamental to the way our ministry works. We are not afraid of innovation, growth, or even failure. We are not afraid of vision and creativity in others. We want our team and the communities we serve to feel inspired and encouraged, to feel their voices are heard and valued, and to feel that we are not a movement with singular leadership, but a leaderful revival with space for all who feel a heart’s call to some form of ministry. We teach each other, and we learn from each other, and we grow together. We have confidence in our gifts and the gifts of others, but no ego. And there is always celebration for one another. We see our ministry as an Acts church, many places and people coming together as one, the body of Christ, the image of God in community.

This is fundamental to the way our ministry works. We are not afraid of innovation, growth, or even failure. We are not afraid of vision and creativity in others. We want our team and the communities we serve to feel inspired and encouraged, to feel their voices are heard and valued, and to feel that we are not a movement with singular leadership, but a leaderful revival with space for all who feel a heart’s call to some form of ministry. We teach each other, and we learn from each other, and we grow together. We have confidence in our gifts and the gifts of others, but no ego. And there is always celebration for one another. We see our ministry as an Acts church, many places and people coming together as one, the body of Christ, the image of God in community.

Yet, this understanding of church, this way of being with one another, has done nothing but strengthened our understandings of priestly ministry, and I hope I can speak for those who work with us, helped shape the discernment and formation of those on our team, and those in our communities who are hearing a call.

We have found great meaning in the holding of sacred space at the center of the circle, rather than an attachment to symbols of privilege and rituals of power. In Indigenous Ministries, we do not go to church on Sunday, we are the church every day. Whether we are delivering free dinners to our elders, or creating a joyful noise with our Gospel Jamboree, or playing games with the community’s children, or sharing knowledge through language classes or basket weaving or life writing or Bible study, we are the church. We are building disciples and equipping our saints, through food and friendship and faith.

Deeply embedded in this way of being is the traditional understanding that ceremony is life. It is the parts that are held in the longhouse or the cathedral, but it is also the parts that are held in the fields and the shores of the sea, the city square and the community center. Everything we do is ceremony, because everything we do shares in the ongoing creation of our universe. Thus, the purpose of any ceremony is to build stronger relationship or bridge the distance between the cosmos and us. So why should sacred space not exist in the grocery store line when someone needs to confess?

By reshaping our concept of sacred space and sacramental ministry, we have rooted our priestly ministry in the mission and life of the community and given room for others to live into their God-gifted purpose as the hands and feet of Christ. For others to find their unique gift to give and their own vocation. It has provided significance to the varied work our communities do, be it visiting the long-term care patients, working with the unhoused and those with food insecurity, or creating learning opportunities for those who have been separated from their traditional ways; and reminded us all that we do the work of Christ together which has given our communities renewed energy and determination as well as a way to envision a futurity that embraces a new way of being.

That futurity of the Indigenous Church, and we honestly believe, the whole of the Anglican Church, however, must be established on newness. And that is the second concept I wish to share this morning: the importance of being new.

There is a famous quote by Audre Lorde that I love: “For the master’s tool will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change”. Now, while that may seem harsh and bleak to some, I think it echoes the Biblical ideas that Christ and St Paul put forth of the Kingdom as being a space of newness, or transformation, revival, yes, but not the simple revival of breath and blood, but the spiritual revival of being unraveled and remade, housed within a body that is not like the one before. To frame this in perhaps more hopeful language, we cannot build a house with the old, rotten boards. It cannot stand.

We can love that old house; we can treasure the memories it holds. We can mourn the passing of time and the inevitable lifespan of finite things. We can even tear apart the old building to rescue and recycle what is still strong and healthy. But we cannot ever rebuild the exact same house.

We can love that old house; we can treasure the memories it holds. We can mourn the passing of time and the inevitable lifespan of finite things. We can even tear apart the old building to rescue and recycle what is still strong and healthy. But we cannot ever rebuild the exact same house.

We in Indigenous Ministries have been actively engaged in the learning of this. Because we know, especially for Ros and me as cradle Anglicans, how heart-wrenching it can be. How complicated our feelings can be around the aspects of church that are no longer life-giving. That are tied to exertions of control and supremacy, that are tied to ideologies of dominance and sovereignty. Which are sometimes very hard to parse out or unravel from our own nostalgia or desires for influence.

Yet, the need for newness in Christ is evident throughout the Gospels and Paul’s letters; a sign of the commitment of his followers to not just walk away from material things, but the willingness to put aside power structures. Newness is integral to the building of the Kingdom, and it is at the heart of the work of the Gospel. To be made new, to shed the ropes that bind us in harmful ideologies, to disentangle ourselves from the social constructs that we have established to limit and exclude. To be made new is the only way forward. We must be willing to be made new, over and over and over again. To become more loving, more gracious, more reflective, more forgiving, more just.

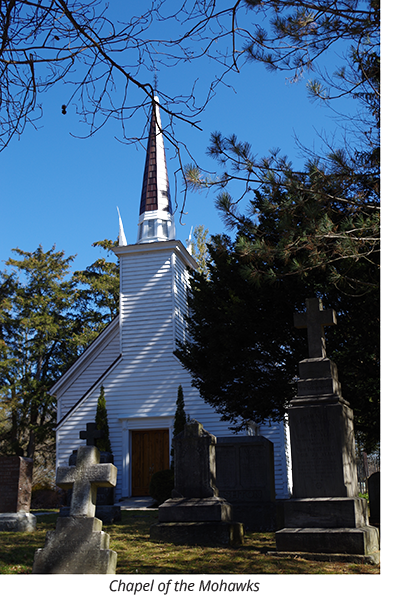

This newness for Indigenous Ministries has been modeled in many ways, big and small, from the removal of the pews in Zion for the creation of a circular worship space, to the creation of cultural revitalization programs and connections with community resources such as the Language centers, to giveaways of dinners, pumpkins, and Christmas presents. We are finding new and revitalized ways to engage with our communities and asking ourselves where we are now and what do our people need today, rather than what used to work, what did we do 20, 50, 100 years ago, or what did we look like when we were full on a Sunday morning. The circumstances in which our churches are situated are not the same as those of decades ago, and the societal environment in which we find ourselves has changed. The solution of yesterday will not necessarily work for tomorrow, and we are having to engage with the question of what are we capable of?

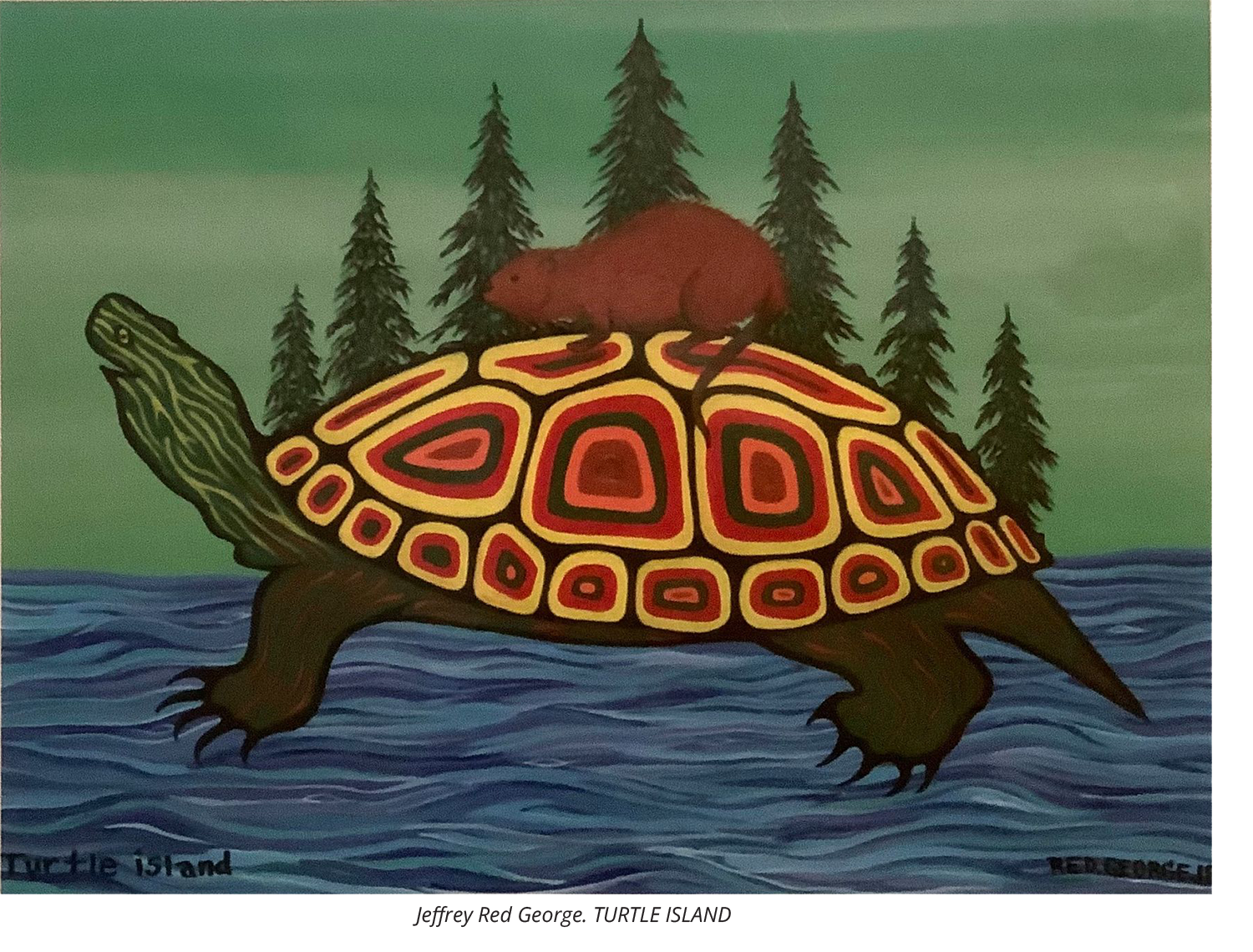

But much like Jesus in Matthew 17 is not to be confined to a tabernacle or a tent by Peter, we are not confined within the walls of our historic buildings or the structures of our forefathers. Like the Spirit at work in the world, we are making community amidst the people. And in this commitment, we are finding new ways to practice the traditional ways of understanding land, place, and space; as we make the landscape of the Gospel the location of our Dish with One Spoon, the long ago treaty made between the Indigenous nations of this area to share the beaver hunting grounds, the resources, and to live and work in cooperative relationship with one another, we can see our dish as the table of the Lord, where we all sit as guests, sharing the gifts given by the Host of the Most High.

And with the mindset of being guests, we can see our purpose in mission and ministry as one of invitation and welcome rather than control or constraint. We are not a museum or a renaissance fair, we are not re-enactors of worship but creating and discovering worship as an outpouring of the community, not the preferences of the priest or the longest members attending. We are reclaiming and reinventing the ways in which we speak symbolically and the ways we interpret story.

That is my final concept that I wish to share from what we’ve learned: the importance of story.

That feels like a very obvious concept to share, and perhaps not one worth mentioning, but I think it is important for many reasons. In this day and age where there is so much discussion around misinformation and disinformation and who has the right to facts and what is an opinion, the need for storytelling is more apparent than ever. Storytelling helps create community, it fosters emotional connection, it shares important information and conveys experiences we do not have access to. It is a fundamental part of humanity. And it is through stories that we first begin to understand the world.

That feels like a very obvious concept to share, and perhaps not one worth mentioning, but I think it is important for many reasons. In this day and age where there is so much discussion around misinformation and disinformation and who has the right to facts and what is an opinion, the need for storytelling is more apparent than ever. Storytelling helps create community, it fosters emotional connection, it shares important information and conveys experiences we do not have access to. It is a fundamental part of humanity. And it is through stories that we first begin to understand the world.

It is through stories that we develop the ability to think symbolically and to speak the language of metaphor and parable. Without the skill of meaning-making and interpretation, we are left without the capacity to think critically about the rites and rituals we use, how the signs and signifiers of patriarchy, racism, colonialism, classism, ableism, homophobia and transphobia, prejudices and judgements exist entrenched in simple actions or words, we abdicate the responsibility to be good interpreters.

In the face of darkness, our stories are essential to creation. Our stories of hope and redemption, our stories of radical love and abundant grace, our stories of salvation and resiliency. And more than ever, it is vital to recognize the stories of those who are often left out of the history books. Storytelling allows for a multiplicity of voice, and the opportunity to listen with open hearts and minds to the marginalized and the traumatized. As someone who works with a few different communities who have experienced both religious and societal trauma, the ability to truth-tell, to express the deep feelings of betrayal and the sadness and confusion of a disruption between the Gospel love of Christ and the actions of the world, has great healing powers.

This is the power of the reconciling church, as Bishop Todd spoke of last night, the power of healing. Yet, what is to be healed must first be recognized as broken, as sick, as in need. With the chance to articulate and communicate the hurt, the pain, we can begin restoration. Thus, it is through the understanding of our sacramental duty first to healing and absolution, rather than a focus on baptism or Eucharist as the entrée into Christian life, which gives space for story.

Story also has, as I mentioned before, the ability to convey meaning and it is a practice of knowledge-keeping. And it is crucial to the process of decolonization to practice storytelling. The need for story to disrupt the quote unquote universal, objective, a priori colonial understanding of the world and interpretation of liturgy, of Scripture, is essential and important praxis to our work.

We utilize Bible Study and Gospel-based discipleship to examine both Scriptural texts and traditional stories in conjunction with each other, holding them in juxtaposition to allow for a more holistic approach to understanding. By looking at the Bible stories through a decolonizing lens, we can investigate concepts like the priesthood of women or same-gender marriage, what is a sin or what does reconciliation really require of us. And yes, all of these are topics that have come up. We can discuss, for instance, how matrilineal society views very differently the role of a woman, or how a people of the land exist in exile when separated from Creator and Creation. We can scrutinize the interpretations that have been given to us, looking at the stories of colonized people through the eyes of colonized people, rather than privilege and power. And we can adopt Indigenous methodology as our guidepost, where we look for relational ways of understanding.

This allows for exploring story as a communal act, where what is shared is important and valuable. We can look for connections between our traditional tales and the narratives of the Bible and begin our interpretations with what joins our understandings. The construal of story through an individualist lens opts to focus on what is rare and unique, but to view story through a collective viewpoint is to understand humanity as linked throughout time and space by commonalities and ordinary experiences. It is to see a diversity of story as precious and indispensable to understanding greater truth, rather than an impediment to a simplified and exclusionary singular voice.

Finally, story can allow us to find our authentic selves. It can give us space to reflect on our past and articulate our way of approaching the world. It can illuminate our deepest, darkest parts and give voice to the quiet joys. It can set us free, it can open our hearts and minds to new ideas and new relationships, and it can heal.

And that, really, is what our decolonization work is about. Healing and reconciliation. Not just for our Indigenous communities, but for all of us. And that work is hard. Really hard. Extremely hard. It breaks your heart, and it cracks you open. But that’s how the light gets in.

What I have offered this morning cannot begin to encapsulate all that our work in Indigenous Ministries has given us, has taught us, and I don’t know if I could, even if I had all day, give you the blueprints for how this healing work, the work we all share, needs to unfold. I cannot say, I can only share these reflections. But I would like to offer a little story of my own before I finish.

Recently, my sister and I lost our grandmother, our Bachan. She was one of the people I was closest to in my family, and she was a touchstone for all of us. She was one of the strongest people I know, even though I teased her all the time. She was a Japanese internment camp survivor. And at the camp she was in, the conditions were extremely rough. But there was an Anglican priest and a group of Anglican nuns who demanded to be let in to be with the Japanese. To teach the children and to bring healthy, fresh food and other things they desperately needed. When she left the camps, my Bachan, having never been Anglican before, looked for an Anglican church. She found one in Chatham, and there, with her Buddhist husband, they found connection and friendship. And the young couples who welcomed them, even though they couldn’t eat at the same restaurants or live in the same neighbourhood, they became family.

I am standing here this morning as proof of the power of loving your enemy. I am only Anglican because of the radical love people of this church showed. And I believe the way I do because I know that there is immense power for healing and reconciliation within us.

We have a long road to walk, and neither Ros nor I have a map, nor does anyone with a title, I hate to break it to you. Where we go we have not been before, but while this road is long and winding, we are going together, and that is something. So, take my hand, and let us travel with hope, with faith, and with abiding friendship.

Rev. Hana Scorrar is Indigenous Ministries Missioner in the Diocese of Huron.